Many people think, as a person with a disability, the thing I want the most is a cure. For a long time, I saw “the cure” as something I clearly needed. At 17, in 1990, newly diagnosed with Friedreich’s ataxia, a rare, progressive neuro-muscular disease, I would’ve pleaded for anything to “fix” me. Life as a wheelchair user scared me and made me think the life I had planned, moving out of Wisconsin, romance, and a career was impossible. But I kept thinking that someday there would be a cure.

In 2000, at 27 and as a new wheelchair user, I worked for the Wisconsin Coalition of Independent Living Centers (WCILC), as the Project Coordinator. I planned events for people all over the state with varied disabilities. Each day, I learned about disability culture, its history, and the ways I was socialized to view disability.

For example, my boss at WCILC described how the idea of the cure implies disabled people are less than and we need to be “normal” to bring any value to the world.

I imagined how changing my body wouldn’t magically transform my life. All my insecurities would still exist—I would still hate the jiggle of my upper arms and continue blushing at the drop of a hat. It wasn’t as if once I sat in my wheelchair or started using my walker, my intelligence, intellectual or emotional, declined.

Soon after my boss explained the cure, I didn’t want anything to do with it and objected to anyone suggesting such a thing. I am not less than,

Being diagnosed in 1990 meant the resources for people living with FA were almost non-existent. I had only met one other person with FA until I moved to California in 2001. I met four other FA’ers, including the mother of one of them. She told me about the Friedreich’s Ataxia Research Alliance (FARA).

FARA sounded like a group I would like. I’d get to meet others with FA and build community. My heart fell when I found out their website is curefa.org. I didn’t want to be associated with an organization that implied I was not good enough.

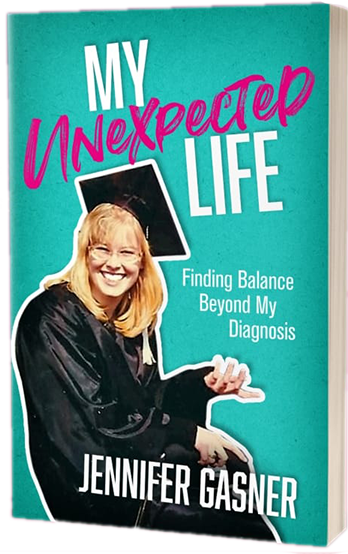

I kept FARA out of the back of my mind until 2020 when I was getting ready to publish my memoir, My Unexpected Life: Finding Balance Beyond My Diagnosis. One of the employees of FARA, Kyle Bryant, who also has FA and wrote his memoir, was going to be at a FARA patient symposium in Anaheim. I wanted to ask his advice about creating a platform and his writing process.

I met Kyle and other people with FA from ages 8-65, as well as parents and loved ones. I noticed the familiarity and camaraderie among all those living with FA. They laughed, hugged and exchanged stories of falling and the dreaded coughing fits that come with FA. And there was no shame. No embarrassment. Just understanding. I realized I felt a fellowship with them and wanted to expand that.

As a result, I made a 180-degree turn and became a FARA Ambassador later that year. An ambassador advocates for FARA research and helps bring awareness of FA to their community. Although I was curious about people’s experience with FA, I was still reluctant to say I wanted a cure.

When I began going to monthly meetings in the group, “cure FA” popped up in signs, t-shirts, and zoom backgrounds. I should not have been surprised, but part of me didn’t think everyone understood they were downplaying their own value and worthiness. I wanted to scream and tell them to stop perpetuating the myth that a cure will make us better people.

I thought I could infiltrate the FARA ranks with my outlook–not needing a cure. How arrogant was I? But instead, my interactions made me reevaluate the idea of a cure and whether it’s so wrong for people to want.

I’ve met many FA’ers with heart complications, a potential life-shortening prognosis. I‘ve heard of people who had to live in a facility due to a lack of support to live at home. If I were in either situation, which I am not, I’d be all in for a cure.

Do I think a cure will fix all my problems? Make life easier? Maybe…

I think more about who I’d be if I didn’t have FA anymore. Would my circle of friends change? Will I use drugs and alcohol more? Maybe…

But I don’t want to get caught up in questioning whether my life would be better or worse. I want to live in the now. While that may work for me, I understand for many, the cure has more complex implications.

Like any aspect of identity, disability is individual and often intertwined with an array of factors like race, socio-economic status, and access to, as well as understanding, of programs for the disabled.

Now, my belief is finding a cure can hold different meanings for different people. I don’t want to dismiss people saying they need a cure. How can I?

The bottom line is I want people with disabilities to consider themselves worthy and to embrace their lives-no matter how messy they look. Living a full life with a disability is possible. I did move out of Wisconsin, I have romance, and I had a career.

At the same time, I want to support others who believe the cure is essential and not be judgmental of their reasoning. Although I have no clear process to reach that point, I am trying to get there.

In my role as an ambassador, I haven’t been in a situation where I’ve had to flat out say, “cure FA.” However, the idea of saying those words isn’t as ridiculous as it was 15 years ago due to my realizations about the intricacies of the cure. Still, I struggle with the thought of saying the words “cure FA,” but now I see the cure is nuanced and there is no black and white answer.

Until the next…

I love your insite, Jen. Your post gives me lots to think about.And to anyone who has not yet read your memoir, I highly recommend it!